Unstoppable: The Enduring Art of Lois Dodd

Lois Dodd demonstrates that art-making isn’t a career or an occupation, it’s a way of life

by Cynthia Close

Most people look forward to retirement, usually starting around age 65, but artists often continue to work, some-times for decades longer, even up until their final hours. Examples abound throughout art history of creatives who were actively evolving—inventing new approaches and exploring new media—in their elder years, even as their health declined. For many people, the act of making art is restorative, providing a font of energy that can be renewed day by day, year after year, enabling them to maintain their productivity as they age.

When the New Jersey-born modernist painter Lois Dodd was asked about her “practice,” she bristled at the word. “Doctors and lawyers have a ‘practice,’ artists have a life,” she said. This interaction occurred during an online interview and discussion with Dodd and artist Eric Aho, in conjunction with the 2020 exhibition “Figuration Never Died: New York Painterly Painting 1950–1970,” at Vermont’s Brattleboro Museum (see a video of the interview at bit.ly/dodd-brattleboro). It was a rare moment interrupting the usually calm demeanor of the 95-year-old Dodd, who sat patiently answering myriad questions from the participating audience members. She was open, thoughtful, and engaged, just as she was during her interview for this article, despite the pressure of preparing for her annual summer transition to Maine.

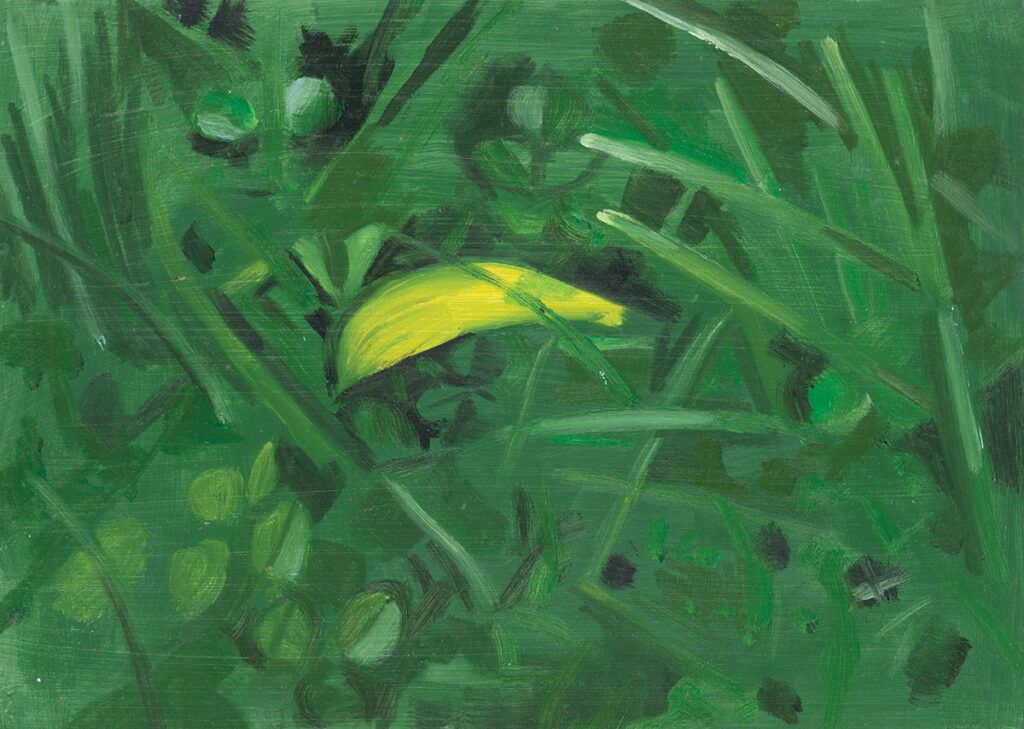

(2010; oil on aluminum flashing, 5×7)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

THE ARTIST’S LIFE

Although Dodd thinks of artmaking as integral to her life—more so than a “practice” or career—certain educational and professional milestones are worth noting.

At a young age, Dodd lost her mother to cancer and, soon after, her father, a merchant marine, died at sea. Fortunately, her older sister was already acting as head-of-household during the father’s voyages, and as such, she was able to preserve some sense of family stability and continuity. The artist attended high school in Montclair, N.J., which she recalls having “a beautiful art room with a skylight.” She learned from her art teacher that she could pursue her creative interests, tuition free, at the Cooper Union, in Manhattan’s East Village. Like her close friend and colleague, Mel Leipzig, Dodd learned her craft at this institution. It was also at Cooper that she met her sculptor husband, Bill King (1925–2015).

Dodd was an active member of the avant-garde Tenth Street art scene, a loose-knit coalition of artist-run galleries operating with low budgets and presenting a 1950s–60s alternative to the high-end, more doctrinaire gallery system. She was the only female founder of the cooperative Tanager Gallery, where she exhibited from 1952 to 1962. The artist supplemented her artmaking with a teaching position at Brooklyn College until her retirement in 1992.

“I can’t invent anything. I need to observe from life.”

—LOIS DODD

Dodd’s first painting to enter a museum collection was The View Through Elliot’s Shack Looking South (1971), acquired by New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. With her usual patience and equanimity, she comments, “If you wait long enough, the world comes to you.”

These days, Dodd’s paintings of scenes from her apartment in New York City’s Lower East Side and from her family home in Blairstown, N.J., near the Delaware Water Gap, as well as views of the woods and gardens around her summer retreat in Maine, are much in demand. She’s currently rep-resented by the prestigious Alexandre Gallery, in Manhattan, and has been included in many solo and group exhibitions since the 1950s, but it wasn’t until 2013, when Dodd was 85, that she was given her first museum retrospective, titled “Catching the Light,” at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, in Kansas City.

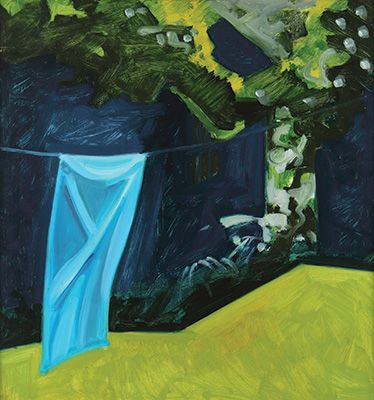

(2011; oil on aluminum flashing, 7×5)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

(1962; oil on linen, 58×65)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

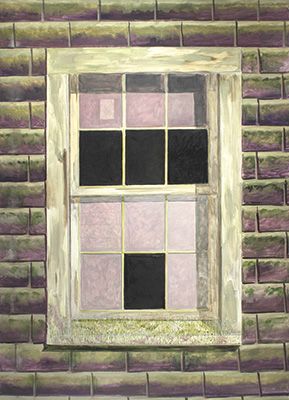

(1982; oil on Masonite, 16×15)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

CHANGES AND CONSTANTS

Dodd’s compositions are a product of, as she puts it, “finding and framing the everyday.” There’s a naturalness, an unforced quality in all the artist’s work. “I don’t want to set things up,” she says. As a result, her paintings feel inevitable—Zen-like. They simply are. The subject matter of her work is broad, but a limited tonal color palette is a signature element running through the artist’s oeuvre.

For her early work, Dodd would make drawings on site and then return to the studio to paint the compositions on a larger scale, using oil on linen canvas. “I tried acrylic,” says Dodd, “but it felt like chewing gum.”

It took the artist some time to adapt to direct painting en plein air without preliminary drawing. She found working on gessoed Masonite panels, no bigger than 20 inches on the longest side, allowed her to start and finish a painting in one outing. “It has to be one session,” she says. “You start and keep going until you finish.”

A student introduced Dodd to aluminum flashing, a roofing construction material, as a painting surface. Dodd, who works alone and has no studio assistant, says, “I like to do all the chores—gessoing and sanding the aluminum surface—myself.” Sunflower Petal in Grass and Night Streetlight, Rockgarden Inn, both painted on aluminum flashing, are little gems.

(1973; oil on linen, 66×54)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

(2014; oil on linen, 66×48)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

(2020; oil on aluminum flashing, 7×5)

© LOIS DODD, COURTESY ALEXANDRE GALLERY, N.Y.

In addition to changing her process and painting surface over the years, Dodd developed her style and compositional approach. Her 1962 painting Pond has a loose, open-air, gestural quality that seems closer in style to the work of Willem de Kooning (1904–97) than to Dodd’s more directly observational, figurative work that followed. Night Sky Loft and Shed Window are large oil paintings—both of which use a window as the primary structural element—demonstrate very different compositional approaches.

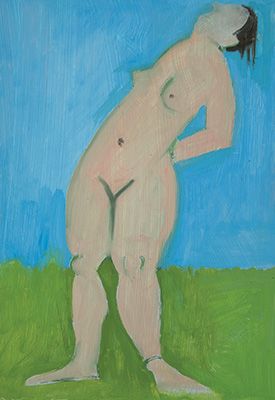

One characteristic that remains constant in her work, however, is an egalitarian approach to her subject matter. In a painting by Dodd, a single piece of laundry hanging on a line holds as much significance as one of her rarely present human figures. Blue Towel is animated by a slight breeze, while in Nude Leaning Back – Blue Sky, the figure is caught motionless, wedged between the top and bottom edge of the frame. Dodd also tends to close in on her focal point. Landscapes, from this artist’s perspective, aren’t grand vistas stretching into far horizons—and her uniform tonal quality obliterates the constant changes of sunlight and shadow, making the image timeless.

In general, Dodd’s paintings are like haiku or meditations. They radiate a peaceful sense of quiet—a place of retreat, which we can all use a little more of in our lives.